The Yoga of Hemacandra's Yogaśāstra

The Yoga of Hemacandra's Yogaśāstra

As I teach my new online graduate seminar on Jain Yoga in our collaborative MA program, I want to share with you some of the fascinating features of Hemacandra's famous yoga text, the Yogaśāstra.

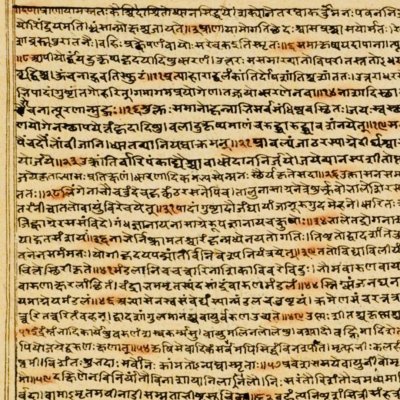

Hemacandra (1088-1172) wrote the Yogaśāstra (12th c. CE) under the patronage of King Kumārapāla of the Caulukya Dynasty in today’s Gujarat. The Yogaśāstra was a highly respected Jain yoga text in medieval South Asia which remains authoritative in Śvetāmbara mūrti-pūja communities (those venerating images) today. Because he was so well learned, Hemacandra earned the honorific title “Kalikāla-sarvajña,” or “omniscient one of the kali age,” and is credited by tradition as having even converted King Kumārapāla, his Śaiva king, to Jainism.

According to Qvarnström (2002), Hemacandra’s likely intention in writing the Yogaśāstra and its auto-commentary, the Svopajñavṛtti, was to espouse an intelligible form of Jainism that Jains, those with whom they lived from other traditions (e.g. Śaivism and Islam), and the state could understand. Such a project involved drawing from existing Jain scriptures teaching yoga and meditation (e.g. the works of Umāsvāti and Haribhadra), combining them with elements of practice from surrounding Śaiva and tantric traditions including Kashmir Śaivism and medieval Siddha traditions, and finally adding in his own yogic experiences for good measure. Significantly, the Yogaśāstra was intended as a guide for spiritual life not only for Jain ascetics, but for lay Jain householders as well.

Organizing Principles of the Yogaśāstra

As Qvarnström has observed, the Yogaśāstra has three primary organizing principles. These include:

- 3 Jewels (ratna-traya) of Jainism: correct worldview (samyag-darśana), correct knowledge (samyag-jñāna), and correct conduct (samyak-cāritra)

- 2-fold Dharma (dvidharma): a structure adapted from the Brahmanical Vedic corpus comprised of the division of action (karma-kaṇḍa) and the division of knowledge (jñāna-kaṇḍa)

- 8-limbed (aṣṭāṅga) yoga from the Pātañjalayogaśāstra (cf. Qvarnström 2000)

Hemacandra uses the first several chapters of the Yogaśāstra to explain the 3 Jewels of Jainism, which he equates with “yoga.” Yoga is therefore primarily comprised of correct worldview (samyag-darśana), correct knowledge (samyag-jñāna), and correct conduct (samyak-cāritra).

The 2-fold dharma (dvidharma) includes first concern with improving one’s conduct in the world (pravṛtti) which leads to happiness (abhyudaya), and second with suppressing conduct (nivṛtti) in the form of cultivating a correct understanding of reality through meditation and resulting in liberation (niḥśreyasa).

Patañjali’s famous 8 limbs provide a third and final organizing principle for the Yogaśāstra. The eight limbs are: yama (ethical restraints), niyama (moral observances), āsana (posture), prāṇāyāma (breath control), pratyāhāra (withdrawal of the senses), dharāṇa (concentration), dhyāna (meditation), and samādhi (meditative absorption). Elements of all of these practices are found in the Yogaśāstra, which progressively bring a yoga practitioner into proper relationship to the world around them and inward toward the liberation of the Self (ātman/jīva).

In addition to these three primary organizing principles, Qvarnström also highlights the Śaiva and tantric influences on Hemacandra’s Yogaśāstra.

Śaiva and Tantric influence on Hemacandra’s Yogaśāstra

In chapters 7 through 10 of the Yogaśāstra, Hemacandra uses, as Qvarnström notes, a terminology and structure that had to his point in history never been used in a Jain text. He likely drew from the traditions of Kashmir Śaivism and other forms of tantra with which his Śaiva audiences would have been familiar with (cf. Qvarnström 2002).

Hemacandra also likely draws terminology specifically from the Nāth Siddha tradition, with whom Śvetāmbara Jains had shared centers for religious practice in medieval Gujarat. Further references to divination practices, for example, show that Hemacandra was also clearly drawing from pan-South Asian influences. He mentions practices like astrology (jyotiṣa), dream interpretation (svapna-śāstra), and animal portents (śakuna), while even mentioning the “sinister yogi” (cf. White 2009) practice of entering into and taking over another person’s body (para-kāya-praveśa).

Why does Hemacandra mention these practices, and with all of these overlapping influences, what makes Hemacandra’s Yogaśāstra particularly Jain?

“Jain” Yoga in the Yogasāśtra

At Arihanta Institute, we have created the subdiscipline of “Engaged Jain Studies,” which from a methodological standpoint considers the ways in which Jains, including Jain yoga authors, engage with their surrounding historical, religious, philosophical, and social environments even as they maintain a commitment to their Jain identity and soteriology. In the process, the Jain tradition is transformed but so too is the surrounding social environment, and this applies specifically to Hemacandra’s Yogaśāstra as we have seen in the work of Qvarnström cited here.

By beginning the text with the 3 Jewels of Jainism and defining yoga as comprised of these 3 Jewels, Hemacandra set the foundation for an authoritative Jain yoga scripture (śāstra). By then adding in the structures of the dvidharma and the 8-limbed Pātañjalayogaśāstra, Hemacandra was showing that his work fit within these broad and well-known frameworks. And by sprinkling in specific popular practices like posture, breath control, and divination, he gave his text an allure that would have been attractive to his non-Jain audiences.

That being said, Hemacandra makes it clear that the tantric practices he mentions, and even prāṇāyāma itself, are not adequate for achieving liberation and therefore only lead to future suffering and rebirth. Instead, one must undertake the further deeper dimensions of meditation which he outlines following the classical Jain framework and which includes both virtuous (dharma) and pure (śukla) meditation and the complete cessation of the mind (citta-nirodha).

By engaging the teachings and interests of his surrounding, often non-Jain religious milieu in the Yogaśāstra, Hemacandra simultaneously incorporates but also subordinates them within his own larger Jain soteriological framework. In doing so, he follows the instincts of Jain yoga authors such as Haribhadra Virahāṇka and Haribhadra Yākinīputra who preceded him, as well as the evolving spirit of anekāntavāda for which the Jain philosophical tradition is so well known.

If the Jain yoga tradition fascinates you as much as it fascinates me, please join me in our collaborative MA program where we offer a concentration in “Yoga Studies” with special focus on the Jain yoga tradition.

REFERENCES & FURTHER READING:

Qvarnström, Olle. 2000. “Jain Tantra: Divinatory and Meditative Practices in the Twelfth-Century Yogaśāstra.” In Tantra in Practice, edited by David Gordon White. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Qvarnström, Olle. 2002. The Yogaśāstra of Hemacandra: A Twelfth Century Handbook on Śvetāmbara Jainism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

White, David Gordon. 2009. Sinister Yogis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Christopher Jain Miller, the co-founder and Vice President of Academic Affairs at Arihanta Institute, completed his PhD in the study of Religion at the University of California, Davis. His current research focuses on Modern Yoga and Engaged Jainism. Christopher is the author of a number of articles and book chapters concerned with Jainism and the practice of modern yoga.

Professor Miller teaches several self-paced, online courses at Arihanta Institute, as well as in the MA-Engaged Jain Studies graduate program

If you are interested in Jain yoga or just want to learn more about Dr. Miller's research and work, register to attend our next MA Info Session on Friday, October 18, 2024 at 9 a.m. PDT.

You can also check out our webpage or email study@arihantainstitute.org for more information.

Dr. Miller's available online courses:

- 1014 | Jainism, Veganism, and Engaged Religion

- 1008 | Jain Responses to Climate Change [Free Course!]

- 1006 | Jain Dharma and Animal Advocacy

- 1001 | Jain Philosophy in Daily Life