Understanding Saṃsāra

Understanding Saṃsāra

While some religious and philosophical traditions focus on the problem of death, Jainism and its adjacent dharma traditions—Buddhism and Hinduism—concentrate on the problem of birth. Even the popular English rendering of saṃsāra as “reincarnation” underscores the central issue of repeated embodiment, for reincarnation can be read literally as “the process of becoming flesh, again”. In Jainism, the ultimate goal is not to become flesh again or even to prolong one’s fleshly life, but rather to avoid post-mortem fleshiness once and for all.

This spiritual trajectory can be confusing if not also implausible to those encultured outside the Jain tradition. In his seminal work The Denial of Death, cultural anthropologist Ernst Becker wrote incredulously: “Religions like Hinduism and Buddhism [and Jainism] performed the ingenious trick of pretending not to want to be reborn, which is a sort of negative magic: claiming not to want what you really want most” (1973, 12). However, the assumed universality of the desire to be reborn (or to live forever) is not easily compatible with a Jain diagnosis of the mundane world that emphasizes the ubiquity and inevitability of suffering (duḥkha) and the potential to attain a superior state of being.

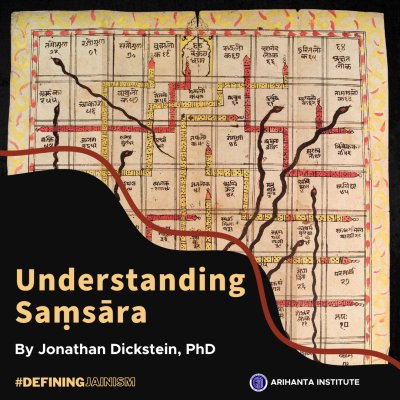

Developed responsively and alternatively to longstanding Vedic ideas, the concepts of karma and saṃsāra were most likely first promulgated by the Jains, Buddhists, and Ājīvikas (Bronkhorst 2011, 7–32). These early śramaṇa (“striver”) groups of the mid-to-late first millennium BCE perceived the mundane world as dominated by suffering no matter one’s station, and one’s recycling into the world—saṃsāra—as the consequence of the accumulation and fruition of karmas. Saṃsāra is a noun derived from the Sanskrit root saṃ + √sṛ, meaning a “going or wandering through” (Monier-Williams). The term refers specifically to “wandering through” the cycle of rebirth and redeath, a process otherwise known as reincarnation, transmigration, and metempsychosis. Importantly, the notion of cyclic individual existence is distinct from cyclic cosmic existence; the latter is an unchanging, impersonal process of the universe while the former is a manipulable, personal process of the individual in the universe.

Jainism asserts that virtually every undertaking involves inflicting some form of suffering upon another sentient organism. This infliction of suffering (hiṃsā) attracts karma particles to one’s soul (jīva) that increases the likelihood of re-embodiment due to the necessary fruition of those karmas. In the absence of any god or supernatural being to intervene in one’s karma “account”, the only way to avoid rebirth is by avoiding new karmas (saṃvara) through the careful performance and minimization of action, and by shedding accumulated karmas (nirjarā) by means of austerities (tapas) such as fasting.

Early Jainism was exclusively focused on the goal of and path to liberation (mokṣa). By eliminating all karmas and thereby emancipating the jīva from its bodily casing, the liberated soul now rises to the top of the inhabited universe (lokākāśa) to join the other siddhas (“accomplished ones”). Disentangled from saṃsāra forever, the soul no longer experiences suffering or inflicts suffering upon other sentient organisms. Moreover, the liberated soul is professed to exist in an eternal condition of pure knowledge (jñāna), perception (darśana), energy (vīrya), and bliss (sukha) (Tattvārtha Sūtra 10.4). Intriguingly, while contemporaneous traditions such as Sāṃkhya also maintained a soul/not-soul dualism (jīva-ajīva in Jainism, puruṣa-prakṛti in Sāṃkhya), Jainism uniquely designates a cosmophysical location for its liberated souls. While the Jain jīva is fundamentally nonmaterial, when liberated it nevertheless remains within the bounds of cosmic space, since “[t]he liberated soul cannot go outside of cosmic space because there is no medium of motion beyond” (Tattvārtha Sūtra 10.8; Jaini 1980, 230).

During its infancy, “striver”-focused Jainism lacked an established lay community and with it any formal reliance upon Jain householders for alms. In addition, early Jain texts repeatedly denounce the lifepath of householders due to its relentless production of suffering and karma (Dixit 1978, 4; Johnson 1995, 23). Jain renouncers regarded all births in the four gatis (human; heavenly being; infernal being; plant and animal), even “good” or “better” births, as undesirable. In short, one’s only “good” birth is their final birth. Nevertheless, as also transpired within other śramana traditions, the development of a lay Jain community and a lay Jain dharma—one that promoted incremental saṃsāric advancement and “auspicious” rebirths—gradually emerged with monastic settlement, social-political expansion, lay patronage, and doctrinal and philosophical innovation.

References

Becker, Ernest. 1973. The Denial of Death. New York: The Free Press.

Bronkhorst, Johannes. 2011. Karma. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press.

Dixit, K.K. 1978. Early Jainism. Ahmedabad: L.D. Institute of Technology.

Jaini, Padmanabh S. 1980. “Karma and the Problem of Rebirth in Jainism.” In Karma and Rebirth in Classical Indian Traditions, edited by Wendy Doniger O’Flaherty, 217-238. Berkeley: University of California Press

Johnson, W. J. 1995. Harmless Souls: Karmic Bondage and Religious Change in Early Jainism with Special Reference to Umāsvāti and Kundakunda. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers.

Tatia, Nathmal. 2011. That Which Is: Tattvārtha Sūtra. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Jonathan Dickstein, Assistant Professor at Arihanta Institute, completed his PhD in Religious Studies at the University of California-Santa Barbara. He specializes in South Asian Religions, Animals and Religion, and Comparative Ethics. His current work focuses on Jainism and contemporary ecological issues, extending into Critical Animal Studies, Food Studies, and Diaspora Studies.

Professor Dickstein's course Jain Approaches to Animal Sentience is available now in the self-paced, online course catalogue.

Check out all Arihanta Institute courses here: